15.3 Elements of dynamic programming

15.3-1

Which is a more efficient way to determine the optimal number of multiplications in a matrix-chain multiplication problem: enumerating all the ways of parenthesizing the product and computing the number of multiplications for each, or running $\text{RECURSIVE-MATRIX-CHAIN}$? Justify your answer.

Running $\text{RECURSIVE-MATRIX-CHAIN}$ is asymptotically more efficient than enumerating all the ways of parenthesizing the product and computing the number of multiplications for each.

Consider the treatment of subproblems by each approach:

-

For each possible place to split the matrix chain, the enumeration approach finds all ways to parenthesize the left half, finds all ways to parenthesize the right half, and looks at all possible combinations of the left half with the right half. The amount of work to look at each combination of left and right half subproblem results is thus the product of the number of ways to parenthesize the left half and the number of ways to parenthesize the right half.

-

For each possible place to split the matrix chain, $\text{RECURSIVE-MATRIX-CHAIN}$ finds the best way to parenthesize the left half, finds the best way to parenthesize the right half, and combines just those two results. Thus the amount of work to combine the left and right half subproblem results is $O(1)$.

15.3-2

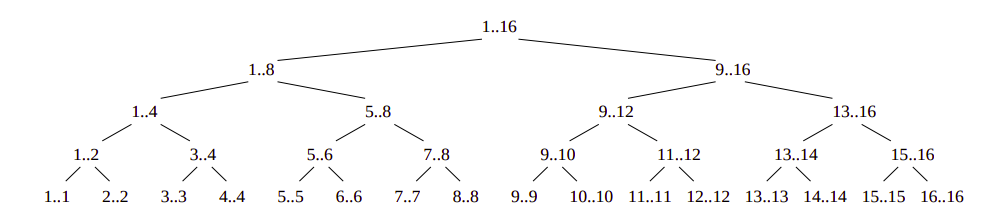

Draw the recursion tree for the $\text{MERGE-SORT}$ procedure from Section 2.3.1 on an array of $16$ elements. Explain why memoization fails to speed up a good divide-and-conquer algorithm such as $\text{MERGE-SORT}$.

Draw a recursion tree.

The $\text{MERGE-SORT}$ procedure performs at most a single call to any pair of indices of the array that is being sorted. In other words, the subproblems do not overlap and therefore memoization will not improve the running time.

The $\text{MERGE-SORT}$ procedure performs at most a single call to any pair of indices of the array that is being sorted. In other words, the subproblems do not overlap and therefore memoization will not improve the running time.

15.3-3

Consider a variant of the matrix-chain multiplication problem in which the goal is to parenthesize the sequence of matrices so as to maximize, rather than minimize, the number of scalar multiplications. Does this problem exhibit optimal substructure?

Yes, this problem also exhibits optimal substructure. If we know that we need the subproduct $(A_l \cdot A_r)$, then we should still find the most expensive way to compute it — otherwise, we could do better by substituting in the most expensive way.

15.3-4

As stated, in dynamic programming we first solve the subproblems and then choose which of them to use in an optimal solution to the problem. Professor Capulet claims that we do not always need to solve all the subproblems in order to find an optimal solution. She suggests that we can find an optimal solution to the matrix-chain multiplication problem by always choosing the matrix $A_k$ at which to split the subproduct $A_i A_{i + 1} \cdots A_j$ (by selecting $k$ to minimize the quantity $p_{i - 1} p_k p_j$) before solving the subproblems. Find an instance of the matrix-chain multiplication problem for which this greedy approach yields a suboptimal solution.

Suppose that we are given matrices $A_1$, $A_2$, $A_3$, and $A_4$ with dimensions such that

$$p_0, p_1, p_2, p_3, p_4 = 1000, 100, 20, 10, 1000.$$

Then $p_0 p_k p_4$ is minimized when $k = 3$, so we need to solve the subproblem of multiplying $A_1 A_2 A_3$, and also $A_4$ which is solved automatically. By her algorithm, this is solved by splitting at $k = 2$. Thus, the full parenthesization is $(((A_1A_2)A_3)A_4)$.

This requires

$$1000 \cdot 100 \cdot 20 + 1000 \cdot 20 \cdot 10 + 1000 \cdot 10 \cdot 1000 = 12200000$$

scalar multiplications.

On the other hand, suppose we had fully parenthesized the matrices to multiply as $((A_1(A_2A_3))A_4)$. Then we would only require

$$100 \cdot 20 \cdot 10 + 1000 \cdot 100 \cdot 10 + 1000 \cdot 10 \cdot 1000 = 11020000$$

scalar multiplications, which is fewer than Professor Capulet's method.

Therefore her greedy approach yields a suboptimal solution.

15.3-5

Suppose that in the rod-cutting problem of Section 15.1, we also had limit $l_i$ on the number of pieces of length $i$ that we are allowed to produce, for $i = 1, 2, \ldots, n$. Show that the optimal-substructure property described in Section 15.1 no longer holds.

The optimal substructure property doesn't hold because the number of pieces of length $i$ used on one side of the cut affects the number allowed on the other. That is, there is information about the particular solution on one side of the cut that changes what is allowed on the other.

To make this more concrete, suppose the rod was length $4$, the values were $l_1 = 2, l_2 = l_3 = l_4 = 1$, and each piece has the same worth regardless of length. Then, if we make our first cut in the middle, we have that the optimal solution for the two rods left over is to cut it in the middle, which isn't allowed because it increases the total number of rods of length $1$ to be too large.

15.3-6

Imagine that you wish to exchange one currency for another. You realize that instead of directly exchanging one currency for another, you might be better off making a series of trades through other currencies, winding up with the currency you want. Suppose that you can trade $n$ different currencies, numbered $1, 2, \ldots, n$, where you start with currency $1$ and wish to wind up with currency $n$. You are given, for each pair of currencies $i$ and $j$ , an exchange rate $r_{ij}$, meaning that if you start with $d$ units of currency $i$ , you can trade for $dr_{ij}$ units of currency $j$. A sequence of trades may entail a commission, which depends on the number of trades you make. Let $c_k$ be the commission that you are charged when you make $k$ trades. Show that, if $c_k = 0$ for all $k = 1, 2, \ldots, n$, then the problem of finding the best sequence of exchanges from currency $1$ to currency $n$ exhibits optimal substructure. Then show that if commissions $c_k$ are arbitrary values, then the problem of finding the best sequence of exchanges from currency $1$ to currency $n$ does not necessarily exhibit optimal substructure.

First we assume that the commission is always zero. Let $k$ denote a currency which appears in an optimal sequence $s$ of trades to go from currency $1$ to currency $n$. $p_k$ denote the first part of this sequence which changes currencies from $1$ to $k$ and $q_k$ denote the rest of the sequence. Then $p_k$ and $q_k$ are both optimal sequences for changing from $1$ to $k$ and $k$ to $n$ respectively. To see this, suppose that $p_k$ wasn't optimal but that $p_k'$ was. Then by changing currencies according to the sequence $p_k'q_k$ we would have a sequence of changes which is better than $s$, a contradiction since $s$ was optimal. The same argument applies to $q_k$.

Now suppose that the commissions can take on arbitrary values. Suppose we have currencies $1$ through $6$, and $r_{12} = r_{23} = r_{34} = r_{45} = 2$, $r_{13} = r_{35} = 6$, and all other exchanges are such that $r_{ij} = 100$. Let $c_1 = 0$, $c_2 = 1$, and $c_k = 10$ for $k \ge 3$.

The optimal solution in this setup is to change $1$ to $3$, then $3$ to $5$, for a total cost of $13$. An optimal solution for changing $1$ to $3$ involves changing $1$ to $2$ then $2$ to $3$, for a cost of $5$, and an optimal solution for changing $3$ to $5$ is to change $3$ to $4$ then $4$ to $5$, for a total cost of $5$. However, combining these optimal solutions to subproblems means making more exchanges overall, and the total cost of combining them is $18$, which is not optimal.